ARTIST STATEMENT

We grow up thinking of other living things and spaces as how they look to us according to our senses. A rock is hard, a lone whale is alone. They are as we see them. But, is that fair? Are you as how I see you? A single whale in the vastness of the ocean may look alone to you and me but whales can whisper to each other across time zones and continents. When we see a single whale we perceive solitude, but that whale may be incapable of knowing loneliness at all. Rocks and dirt may seem dull and lifeless, hard and steadfast to us. But they are full of life and movement on another timescale. They record and show us glimpses of living pasts — moments much greater than our own.

I paint to escape myself and find refuge in imaginings of nature. I like to explore sensory relationships with ecosystems — not just how they are to me, but also how they may be experienced by the organisms that inhabit them; their textures, temperatures, densities, tastes, sounds and smells. This gives me a healthy reminder of my smallness and human limits. There is a certain freedom in that. As a medium, I use primarily acrylics on canvas because they are simple but also lend themselves to a wide variation of textures and application techniques. This flexibility lets me easily switch modes to maintain focus on exploring a connection or perspective.

ARTIST BIO

I am a TV personality, environmentalist, and best-selling author based in Seoul, South Korea. Originally born and raised between the Taconics and the Green Mountains of the northeast United States, I have always felt a strong emotional and existential connection to nature. In my art, I explore that connection as a way of overcoming my own emotional and psychological limits and coping with the loss that I feel in city life.

I have spent the majority of my professional life in educational media, entertainment, and the public sector. As such, I am not an artist by trade nor have I had a formal education in the field any more than any other student would in primary and secondary school. But honestly, I don’t really care about that. For me, making something isn’t for other people. It’s a form of self love and is only for me. I have always felt that way. Since I was little, I would draw or paint because it was fun and made me feel good. As I grew older, that habit stayed with me and became an outlet to refresh and acknowledge myself. Art is still just for me and I will continue to take that with me throughout the rest of my life.

In terms of media, I tend to paint with acrylics. As tools, I use anything I want to play around with. Sometimes I will apply paint to the canvas using tape, leftover plastic packaging, rags, pencil butts, broken pieces of wood, shoe buffers, and more. I also combine random objects to make new tools for application.

PORTFOLIO

Acrylic on Canvas

Ink Pen on Paper

Procreate

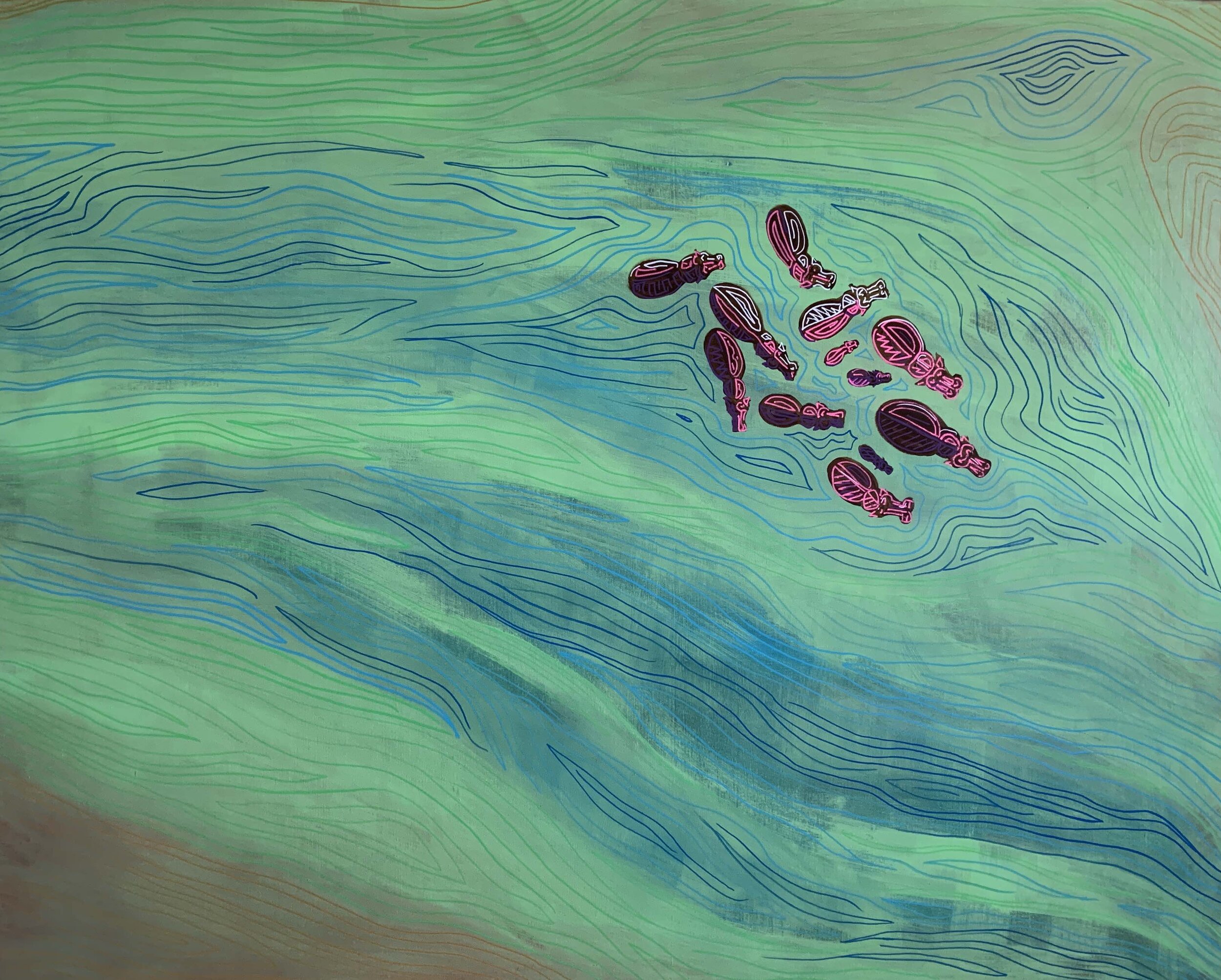

Hippopotamus

Hippopotami (hippopotamus amphibius) play an integral role in sub-saharan ecosystems. They live both in still and moving bodies of water ranging from rivers to lakes and swamps. They spend the day resting and cooling off in groups in the water and then move onto the land at night to graze. As they eat the low-lying grasses, fallen fruit, and other nearby flora, they absorb nitrogen and phosphorous into their bodies. Those nutrients are then later transferred into the water as they relieve themselves. This is why the hippo is called a “cross-boundary species”, because it lives in both terrestrial and aquatic habitats but also links them through eutrophication. Without the hippo, aquatic ecosystems would suffer and so would, in turn, surrounding ecosystems. For this reason, hippos should viewed with reverence. They are a key, integral species and one of the most important eco-architects on the African continent.

We think of hippos as fat and, yes, they do have a lot of fat on their bodies. But, they also have a very robust skeletal structure. Without taking a look at the skeleton, one would assume that hippos don’t really have necks. However, that’s not true. As land-based grazing animals, they actually have longer necks equally as long as their front legs. It just doesn’t look like their necks are long because they also happen to store a lot of fat in that area as well, making it, when viewed from above, look more like their shoulders. Hippos are related to pigs and whales, which is also reflected in their skeletal structure and the way that they interact with the surface of the water.

How could we portray hippos from above when they are in the water? While they graze alone on land, they are always in groups in the water. Usually, these groups are made up of 10 to 30 individuals, mostly females with one dominant male. From above, they group together with their young in the middle. While the whole group is usually oriented in a general direction (a grain, so to speak), each individual is facing their own way. From above, the body of the hippo may not be visible as it may be entirely below the surface. When hippos break the surface it is usually in the order of nose-eyes/ears-neck-back. Sometimes they will sit at the surface with just their faces above the waterline, sometimes their whole head and spine. When a hippo goes underwater it will, again, leading with its head, go below the surface and sometimes may just expose its back to the air. However, in general, the most common position is head, neck, and back all slightly above the waterline. This makes their outline almost look like ants because the three main body parts have a similar proportion to head-body-thorax when viewed from above. Hippos’ bodies have very unique functions. Given that they spend the majority of their lives under the hot sun, their skin and body temperatures must be regulated constantly. By staying in the water, they can more easily keep their body temperatures low. They also sweat continuously. This sweat also helps protect their skin from sun damage, much like a natural sunscreen. The color has a pink tinge. This is why some people say that hippos “sweat blood” (it’s not actually blood). It’s also another reason why we often think of hippos as pink, when the majority of their bodies are really a darker, purple tone.

Water always has movement to it, whether “still” or not. This movement is both affected by- and helps to determine- the movement of whatever is in the water. In other words, hippos both as individuals and as a group have a mutually influential relationship with the structure of water systems. Hippos help craft the body of water through nutrient transfer and they also benefit from the further development of that body of water. Placement, therefore, needs to reflect this type of relationship.

In order to portray depth and movement of water, layering is necessary. Land, sediment, currents, and depths must be expressed and hippos must be placed appropriately in this matrix.

Current and flow occur in multiple dimensions. It is not just at the surface, but also woven up and and down in columns. When viewed from above, this could be well expressed through the use of various tones and interwoven lines.

The hippos themselves should be grouped. Their body structures should reflect they way they are most often seen in their environment. The light reflected on their bodies and their shape and texture could be well expressed by using geometric lines in various tones.

Octopus

The octopus is one of the earth’s most fascinating creations. So fascinating, in fact, that it has inspired science-fiction, fantasy, political, and philosophical works. Perhaps this is because the octopus has such a unique biology and anatomy topped off with remarkably impressive intelligence. Octopuses (not octopi as the word comes from greek not latin) are cephalopods, which means head-foot animal and encompasses the squid, the cuttlefish, and the nautilus. Octopuses have eight appendages with the mouth at the center, which has a strong beak for breaking open shellfish and crustaceans. The eyes sit just above the mouth. The brain, wraps around the mouth like a doughnut. Compared to all other invertebrates, the octopus has the highest brain-to-body ratio with a highly advanced nervous system.

What many people mistake as the “head” of the octopus, the large sack-shaped part on the opposite end from the arms, is actually the octopus’s equivalent of a torso. That is where all the vital organs are located. That is why when an octopus moves, it does not lead with that part of its body but rather with what we see as the “center” of its body, the eyes. Often an octopus will sit or move on its arms, dragging its torso behind it with its eyes elevated. When the octopus moves, its arms form various different shapes both independently and as a whole.

Thanks to the octopus’s highly developed and decentralized nervous system, each arm can react independently as the octopus moves across the ocean floor. Just as we walk without thinking much about how we move our feet, the octopus can move its arms in multiple different directions, reacting independently to obstacles and stimuli, without having to give much thought to what it is doing. In other words, the octopus is “multidexterous”, so to speak.

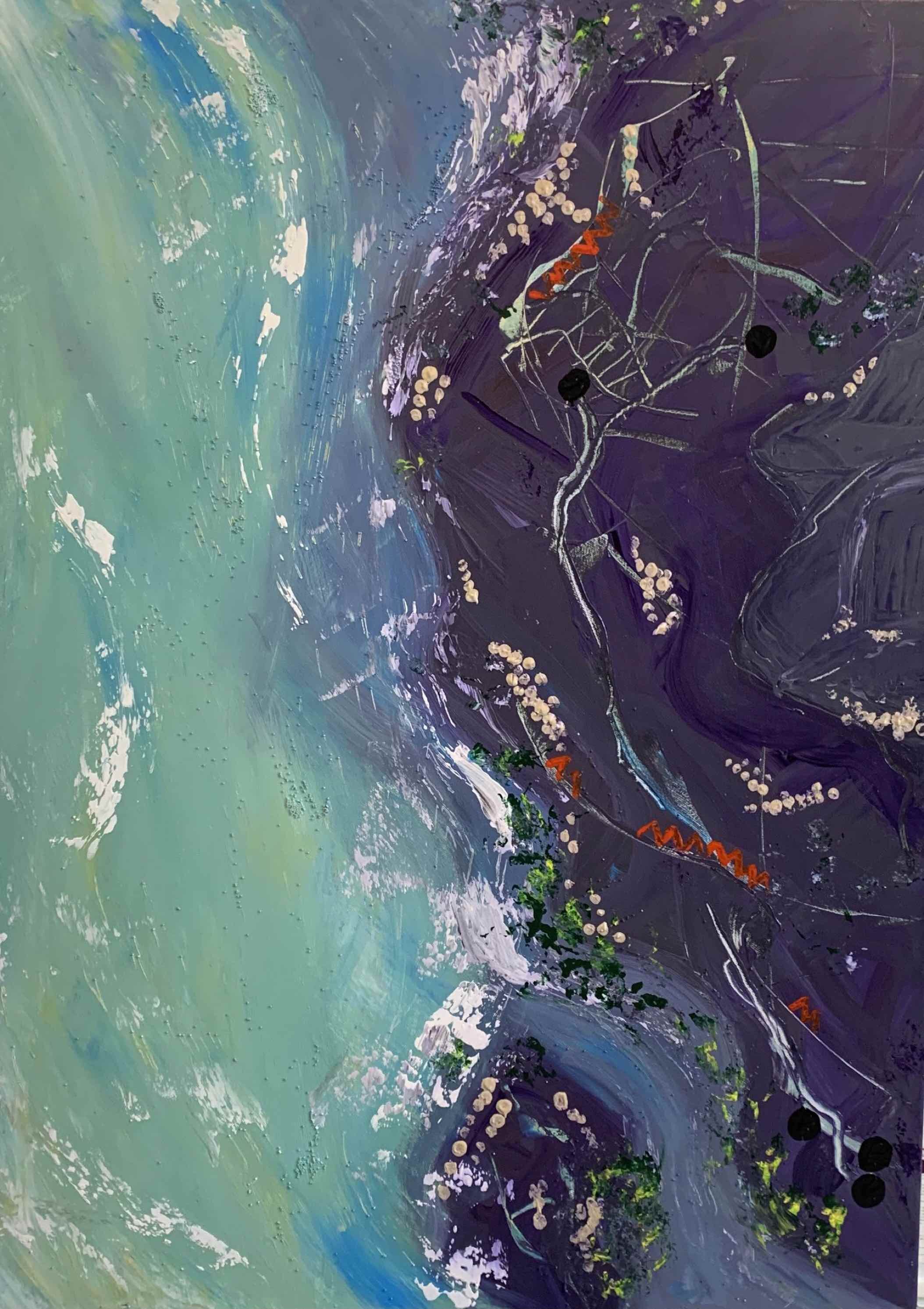

Octopuses live in every ocean on the planet. They are often found in coastal habitats that have diverse and flourishing sea floors. Thanks to their adaptability, they can also be found at extreme depths in the blackest parts of the ocean even as far down as more than 4 kilometers below the surface. However, no matter where or at what depth, the octopus lives primarily on the sea floor where it hunts, hides, and has its young. The sea floor, or seabed, is therefore a very important part of the identity of the octopus. It would be illogical to portray an octopus suspended in the water column because that is not where it spends the majority of its life nor does it depend or have a good relationship with being suspended or swimming through the water. Those moments are usually for fight-or-flight situations. As such, the seabed must be the main focus of the painting because it is the base of the octopus’s perspective and the stage of its life. Seabeds have multiple textures; smooth, sharp, rough, and slippery. There needs to be good mix of organic and inorganic material. Yellows, blues, purples, some red, greens and more. The out-of-focus glance should be a dark purple-brown feel. But, up close, there should be more detail and each color should hold its own.

The octopus adapts its skin color to its surroundings for communication, play, attracting a mate, camouflage and more. The octopus will feel its way across the seabed and can taste everything it touches with the hundreds of suckers on its arms. The amount of information that the octopus will process must be of massive quantities and it is then reflected in its movement and coloration. The octopus is, essentially, reading the seabed and trying to become one with it as it hunts or hides. In a painting, therefore, there should be an overall congruence between the make-up of the octopus and its environs. The seabed should unite smoothly and naturally with the octopus and there should only be a suggestion of its presence. By using tape and then removing it, we can create a white contour of the octopus’s movement without disrupting the textures and colors that will connect the seabed as a whole.

Eons

Cliffs and rock faces expose the places we stand as not just physical locations but temporal ones as well. Rock is something we understand physically as solid, steadfast, reliable, unmoving, hard, lifeless, and cold. That is just a result of our laziness and unwillingness to understand rock on its own timeline. Sedimentary rock, formed over millennia at the bottom of oceans and forests, store the ghosts of another time, another world that was not our own. By looking into the layers, shapes, and textures of exposed rock faces, we can take a glimpse into not only the history of our planet but also learn the secrets of the past.

Sedimentary rock forms, typically, in flat lines of varying textures and thicknesses. They are compressed upon each other and seem, at first solid. But, at a closer look, one can see that there is movement. Surfaces are not always flat, as such the layers of history in these rocks is not always a straight line. Sometimes, they are even interrupted by shifts in the earth, tremors, wildfire, and hurricanes, and flash-floods. Each layer holds within it the flora and fauna of the age. It could have been an ocean floor covered with crustaceans and mollusks, armored fish, and ichthyosaurs. Another layer could be a boggy swamp or a thick forest of early trees in the Carboniferous with centipedes the size of a bus. Yet another later just a bit higher could be resting place of a sweeping plain roamed by gigantic predatory flightless birds (Phorusrhacidae). Each era has its own texture, its own identity, color, and thickness reflecting the many worlds that our earth has hosted — solid records of the most fluid thing in the universe; time.

A tall canvas would be ideal to portray a wide array of layers of rock/time. Each layer needs its own color and texture. Application methods and tools should vary. In order to prevent each layer from encroaching on the next, the painting must be executed slowly, painting 2-3 layers in different sections at a time. In order to more easily keep track of height, depth, and direction, the canvas should first be prepared with a gradation as a background. Then a few black lines of varying thickness and movement should be strewn across the canvas for placement. At the top, layers should be thicker and less varied with more browns, greens, and yellows to reflect the initial decomposition of organic matter. As the painting progresses farther down, other colors like grays, browns, blacks, and even bright tones should be interchanged. There should also be similar tones next to each other on occasion because natural ecosystems often evolve in a way that makes sense and shares a history with their predecessors. There should also be a few spots in the painting that break the typical horizontal layering and maybe include a bit more of a wave or a sandwiched edge. It is important to keep in mind that we are looking at a cross-section of a massive amount of time, multiple eras. Because this rock face is a physical cross-section of that in space, we may only see part of an era protruding forward towards us. This is a two dimensional representation of a three dimensional phenomena that stores a fourth dimension of time.

Identity should be clear from a distance but also from up close. Each layer should be fascinating in its own way and have its own attitude. Application of the paint should include brushing, dabbing, scraping, slicing, and scarring. Paint brushes, shoe brushes, paint knives, and anything else both precise yet variable should be used. When someone gets close to the painting, each area made up of a few layers should also form its own picture. It should be like multiple paintings within one work, just like a rock face is multiple times within one exposed surface.

Whale

How do whales interpret comfort? What does “together” mean to a whale? Whales may seem lonely to us in what we perceive as the vastness of the ocean. But, some whales can whisper tens of thousands of kilometers. To a whale, being “with” someone has a whole different meaning. In order to understand a whale’s relationship with space and the emotions that follow we must first examine its anatomy. Cetaceans are usually split into one of two categories; toothed whales and baleen whales. For the purpose of exploring solitude and space we will explore the perspective of the latter. Their bodies, as descendants of land-based mammals, have a skeletal structure that results in an up and down movement as they swim. Unlike fish, which move from side to side, the whale’s spine is designed for vertical movement. The ribcage is large and, as a baleen whale, the jaw is enormous, almost equally as large as the ribcage. The eye is place slightly more forward than the blowhole. The eyes are also usually situated just at the corner of the jaw.

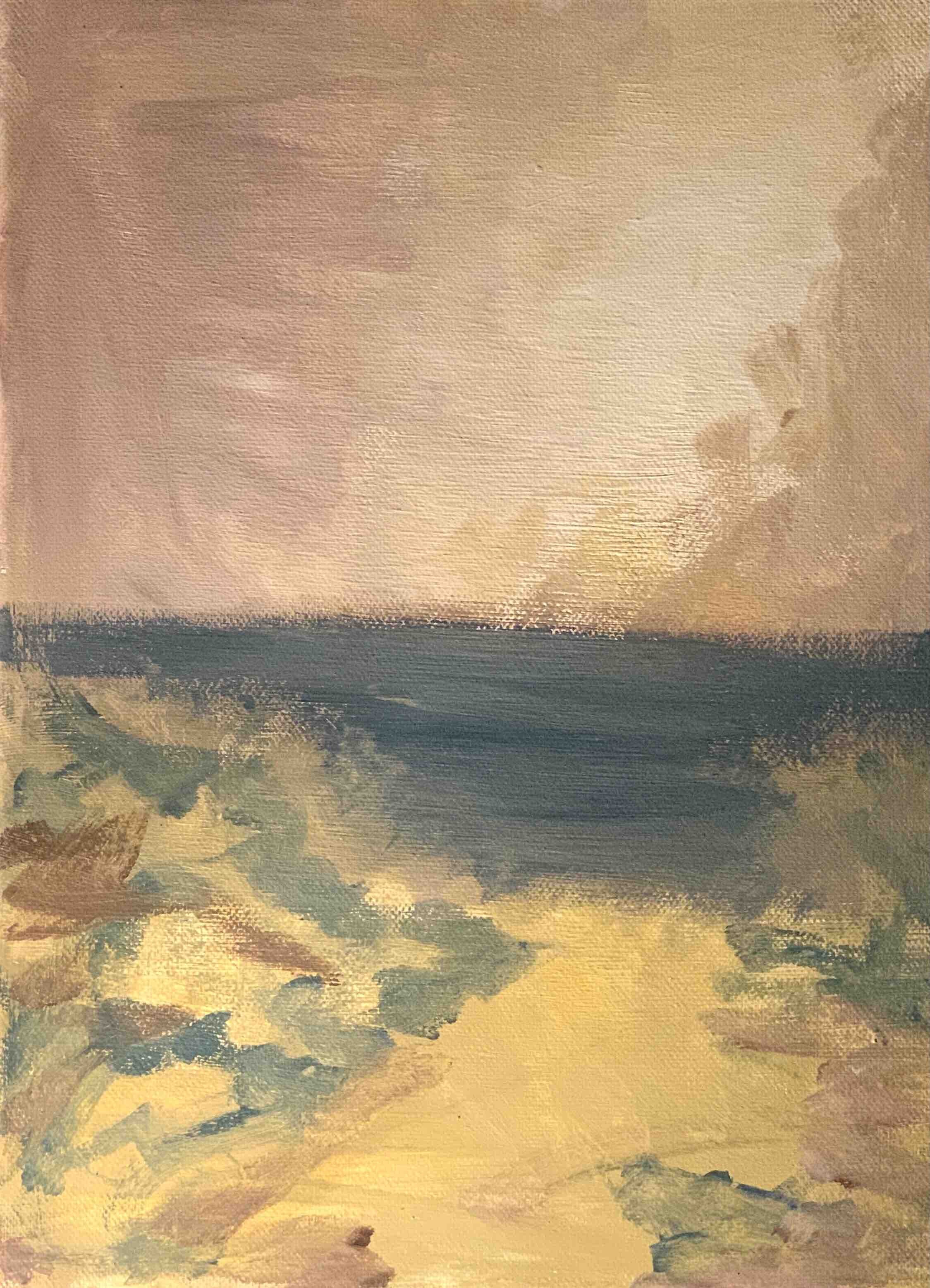

Baleen whales do travel and hunt in pods, however, less so than their toothed counterparts. They also spend a good deal of their time alone or in couples or small families. Large baleen whales can communicate across hundreds and even thousands of kilometers. They do so for mating purposes as well as to indicate hunting grounds to others. In order to show the lone whale in a large space, it should be relatively small on the canvas. Whales may seem big to us, but they are not really very big when you think about the vastness of the ocean. That physicality needs to be emphasized through size and placement.

The ocean itself is made up of many layers of temperatures and currents. They are circular, spinning, twisting, turning, shooting, and interwoven within each other. Using different types of brush strokes, paint thickness, and application techniques (brush, acrylic pens etc.) we can express the diversity of texture, speed, and temperature of these currents.

Depth is also an important concept in portraying the space that the whale inhabits. It does not live on a two dimensional plane as we do with only forward, backward, right, and left. Whales live with up and down. They move in those three dimensions and engage with all those layers of the ocean much like a bird rides swells of air through the sky. The painting needs to suggest that type of depth. The interwoven layering of currents described above can help do that. But, the painting should also have a few base layers. First a layer of different colored gessoes. Then a few layers of different washes. Then on top of those different layers of thicknesses and colored washes, we can add the currents and create a true sense of depth. Dark purple tones will help show deeper water, lighter yellowish-green tones would be warmer and closer to the surface.

Dirt

One of the things we never think about is what lies below our feet — dirt. The word itself even has connotation of being useless, ugly, or unwanted. We give it nicer names like soil when want to use it for growing things. But, in reality it’s all just that — dirt. Dirt is one of the most important things on the planet. It has a lot organic matter and serves as the canvas on which life is painted, much like water does. Take a close look at dirt and it is full of useful nutrients, microorganisms, and fungi.

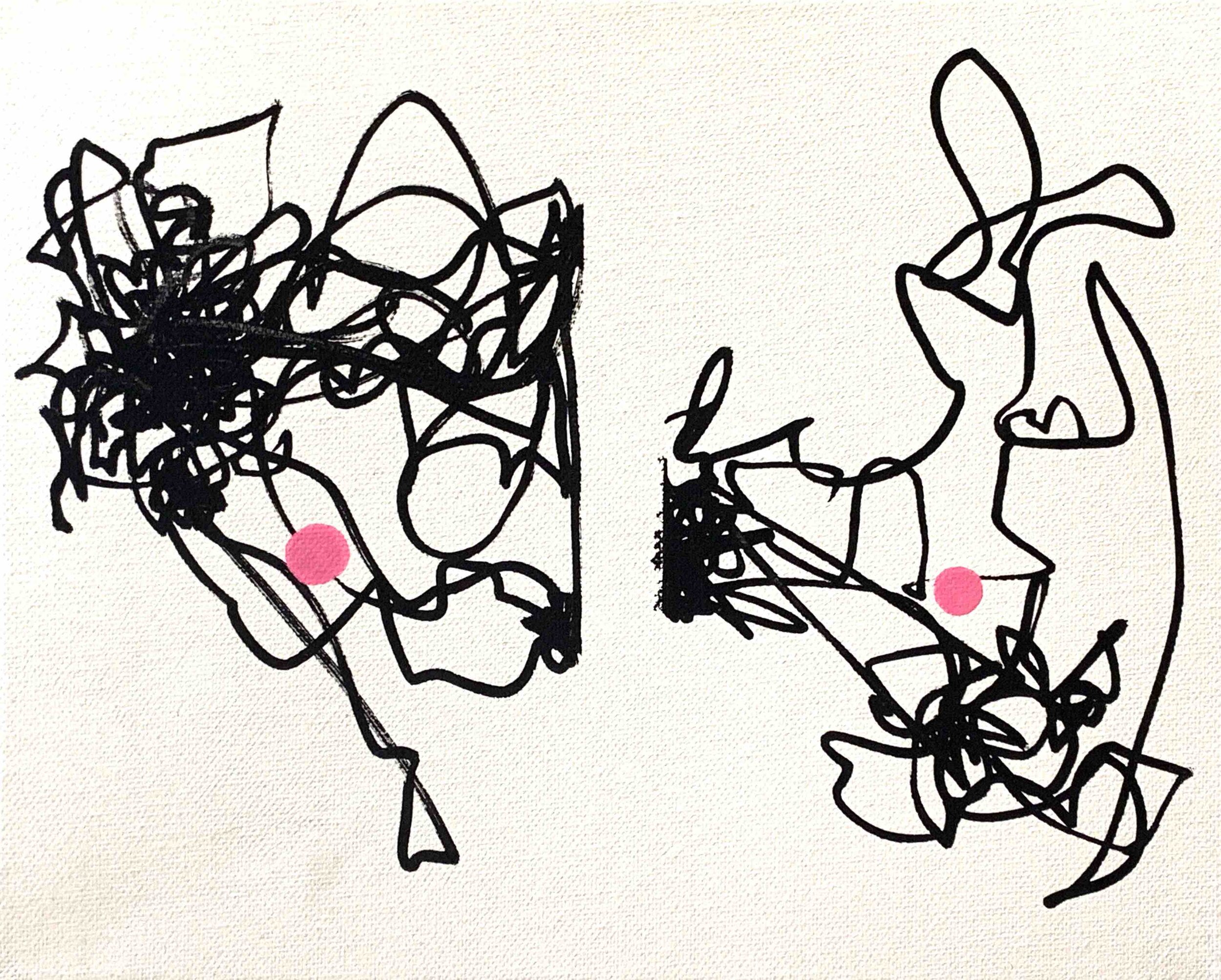

Fungi are everywhere in dirt. Their mycelium, particularly that of mycorrhizal fungi, connects entire ecosystems in a web of nutrients and information. Any piece of dirt you look at under a microscope will be home to many diverse organisms and nutrients. The painting should strive to show this fullness and diversity.

As mycelium interconnect, they form hubs. Different types of fungi are present, so different color hubs should also be present in the painting. They should interconnect and exchange nutrients between each other. Using dots, lines, and other shapes to portray nutrients, we can place these in different concentrations at both hubs and along the long, intertwined connections between them. Each hub should exist as its own entity with its own network, yet they should also be connected as a functional whole and it should be clear to the viewer that they are moving and exchanging something.

In order for nutrients to be exchanged between hubs it first must be collected from somewhere. There should be a section of the painting where the mycelium seems to collect stray nutrients from a space within the dirt and bring it into its system. These nutrients, in the same shape and color, should also be found randomly throughout the dirt but be clearly concentrated along the highways and hubs. Exchange is also an important concept here. Nothing in nature is for free. There is always a give and take. Each hub and network according to its color should be seen as collecting and distributing the nutrient of its corresponding color. In order to get other nutrients, it cannot absorb them directly so it must exchange for them. So, it intertwines with other hubs’ mycelium and obtains nutrients corresponding to those other colors. Brown gets white nutrients from the white mycelium in exchange for brown nutrients from the brown mycelium. However, since they are interconnected, we should also think about third party generated nutrients being exchange by two indirect parties. In other words, maybe white will give white nutrients to the brown network in exchange for yellow ones, which the brown in turn got from the yellow hub. This would make the network look more integrated and more clearly reflect the functionality and dynamic interactions that exist within the dirt.

Big Rock

My mother’s family came from the ocean. They lived on islands in the middle of deep blue water, built boats, made sails, and crossed the ocean to settle on the South Shore by the familiar scent of tides and brine. Although the ocean was never home for me, I did spend every summer of my life as a child visiting that place with my mother, grandmother, sister, and cousin. When they slept in the sun I would wander off to find life clinging to the fine line between the land and the sea. There was a big rock down the beach from our spot. We called it Big Rock. Other people did too. Low tide would leave Big Rock easy to walk to. High tide would embrace it from every side, fill its pools, and keep it from my prying eyes. But, whenever I could, I would climb Big Rock on all fours and peek into every nook and cranny to find whatever treasures scuttered and stuck to its surface.

But reality and memory are never the same. Looking back at photos of Big Rock revealed that really it was never that big. I was just quite small. Perhaps that’s why people like to live in their heads so much, it’s usually nicer than how things really were. What are the things that I remember from that place? What was the Big Rock to me as a child?

Warm thin water, overlapped waves receding into cold black salty depths, undertow. Man-of-war, purple entangled, hard to escape. Rock. Solid. Cold, wet, slippery, salty, smooth and spiky, barnacles. Come down from there. Be careful. Just a minute. Life. Breathing, pools of yellow red green, orange. Quick movement, slow pulse. Another wave coming in.

Portraying Big Rock from my perspective as child would mean mostly looking at where I would first climb up on it. A bit to the left, looking down into the waterline, watching the slow low-tide waves feed the tidal pools. Texture is key. It was a smooth rock, mostly, worn from the waves. Big Rock weathered many hurricanes. But, there were barnacles and periwinkles all over, giving it a rough spikiness here and there. There were a lot of creatures around the rock; seaweeds, jellies, man-o-wars, crabs, snails. For some reason I don’t remember seeing any gulls on the rock. Maybe it’s because I was always climbing all over it.